2025 will inevitably be known as a tumultuous year in Arctic politics, and potentially a turning point as well for roles of Track II diplomacy in the far north. Track II diplomacy itself has often been described as interactions between sub-governmental actors (academics, journalists, researchers and specialists, for example), and sometimes government officials who participate representing themselves but not necessarily their administrations. The impression being that these types of interactions can, albeit indirectly, affect decision-making by governments. This type of diplomacy as often practiced in regions where ‘Track I’ (government-to-government) diplomacy is either blocked or politically difficult, and so it is no accident that Track II is often studied in relation to East Asian and Southwest Asian milieus.

As the Arctic became an area of greater international interest, as well as a focus for global concerns about climate change, Track II initiatives began to flourish in the region over the past two decades. However, in judging the success of Track II in the Arctic, several questions need to be weighed, as with case studies from other parts of the world. How well has Track II affected positive change in cooperation on the governmental level? How receptive are governments to Track II initiatives, and under what conditions? Can Track II be effectively insulated from disputes and tensions on the Track I level?

For more than a decade, Track II conferences which brought together Arctic specialists from multiple disciplines prided themselves on providing ample space not only for information exchanges about pressing environmental issues in the Arctic, but also for frank policy deliberations. These dialogues were challenged after 2014 when Russia annexed the Ukrainian territory of Crimea, and further contaminated when Moscow began its full invasion of Ukraine after 2022.

The shadow of that conflict, and worsened relations between Russia and an expanded NATO, have continuously hovered over Track II endeavours in the Arctic over the past few years, but recently two other regional trends have also affected sub-governmental dialogues, namely the growing interest of the BRICS+ nations in the far north, and the return of the Donald Trump administration in the United States and Washington’s lurch back towards isolationism and hyper-nationalism, linked with a growing anti-science stance.

The ‘competing securities’ problem in the Arctic, namely the struggle for attention between traditional concerns in the far north in the form of environmental and human security, and the ‘return’ of great power strategies and geopolitics, was very much felt at the Arctic Circle Assembly (ACA) in Reykjavík this past October. As with the assemblies in the recent past, there was a tilt in priorities this year, not only towards more overt discussions of hard security, but also the role of non-Arctic states in the region and the economic opportunities which have appeared.

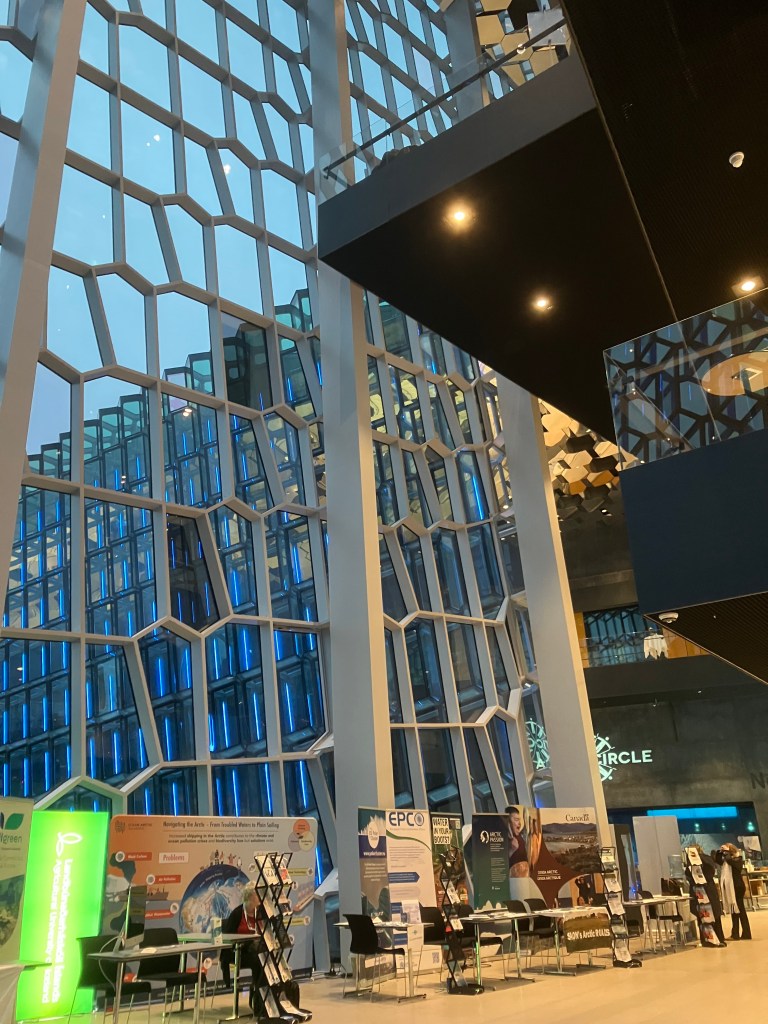

This year’s ACA, chaired once again by former Icelandic President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson, was held in tandem with the Arctic Circle Business Forum, based at the luxury Edition Hotel, next door to the main conference venue at Harpa. Another trend which continued this year was a greater role for plenaries which featured numerous high-level governmental officials, including the Prime Minister of Iceland, Kristrún Frostadóttir, Greenlandic Foreign Minister Vivian Motzfeldt, and Princess Takamado [video] of Japan (who spoke on the importance of understanding climate change, human security challenges, and global scientific cooperation).

Although government delegations have never been rare at the ACA, and indeed many non-Arctic state governments have made use of the venue to advertise their Arctic credentials, this year further cemented the Assembly as ‘Track 1.5’ rather than Track II. As well, in keeping with the growing interest of the ACA in further engaging partners in the Asia-Pacific, other featured plenary speakers including officials from India, Japan, Singapore and South Korea. All of these countries became Arctic Council observers in 2013, and they have sought to place their own distinct stamps on regional diplomacy, with New Delhi and Tokyo having hosted Arctic Circle conferences in the recent past.

There were, however, two major Arctic players with a considerably reduced presence at the conference this year. First, although China was featured in panels covering regional science diplomacy and the work of the Sino-Icelandic research station at Karhóll, northern Iceland, the delegation from the People’s Republic was unusually small and subdued. However, there was one representative from the PRC, a representative of the Department of Treaty and Law within the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, who was active throughout the conference in commenting on any perceived misconceptions regarding his country’s Arctic policies, (he got into a short debate with this author on the importance of China’s early signature on the Svalbard Treaty, in 1925).

It can be argued that China’s Arctic policy is undergoing a reset of sorts, reflecting Beijing’s push for great cooperation in regional science diplomacy as well as attempts to jump-start the Polar Silk Road. During September-October this year, the Chinese container vessel Istanbul Bridge (Yisitanbu’er qiao hao 伊斯坦布尔桥号) made a successful transit of the Northern Sea Route from Ningbo to the British port of Felixstowe. This voyage, extensively covered in the Chinese press, was seen as marking the beginning of Beijing’s planned ‘China-Europe Arctic Express’ (Zhong’ou beiji kuaihang 中欧北极快航) initiative.

With political and strategic uncertainties surrounding traditional maritime transit routes, including the Malacca Straits, the Red Sea, and the Panama Canal, the Chinese government has recognised the NSR as a lucrative emerging alternative transit route. However, with the Arctic becoming further militarised, and Beijing continuing to walk a fine line between cooperation with Russia and maintaining stable relations with other Arctic states, the short-term trajectory of Chinese engagement of the Arctic may still be difficult to measure.

The American presence at the Arctic Circle was also very much reduced, and this was a product of both the government shutdown (the longest in American history, so far), taking place at the time which discouraged travel by officials, as well as the shifting political winds in Washington which has discouraged engaging in official dialogues about climate change, which is still seen as a fiction by the current occupant of the White House. The most recent US National Security Strategy, published last month, left little doubt on that point, as it included the line, ‘We reject the disastrous “climate change” and “Net Zero” ideologies that have so greatly harmed Europe, threaten the United States, and subsidise our adversaries.’ Earlier this month, a largely incoherent speech on the state of the US economy by the president referred to the ‘green energy scam’ while touting ‘big beautiful coal’ and the importance of fossil fuels to the US economy.

This denial policy, coupled with frosty relations between the US and other Arctic states, notably Canada and Denmark, damaging tariff policies, and erratic commitments to assisting with European security threats, have all served to weaken the United States’ stature in the far north during this year.

As with previous years, one of the keynote speeches at the conference was from a senior representative of NATO. In his first appearance at the event, Admiral Giuseppe Cavo Dragone, Chair of the alliance’s Military Committee, spoke [video] about NATO’s expanded role in protecting Arctic lands and seas, and addressing the threat of the region becoming a ‘Sahara scramble, a zone of rivalry, exploitation and conflict,’ unless cooperation and the rule of law could be maintained.

Unlike previous NATO speeches at the ACA regarding the depth of Sino-Russian cooperation in the Arctic, Admiral Dragone was comparatively more circumspect on the issue, suggesting that there was a difference in perception between the two powers. Moscow, he suggested, regarding the pairing as a marriage, while Beijing viewed it as more of a love affair.

In another example of the growing shadow of geopolitical concerns over the ACA, Maria Varteressian, State Secretary – Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, went off script [video] during the question-and-answer session on ‘Norway in the High North’, and used her speaking time to present the country’s newest Arctic strategy paper, published in April this year. (President Grímsson, chairing that session, appeared perturbed at the sudden change in format, and pithily remarked that it was examples like this which explained the centuries of ‘problems’ between Iceland and Norway).

Despite the compressed schedule of the ACA this year, there were still several panels and exhibits dedicated to environmental issues, such as plastic pollutants, changed weather patterns, and renewable energy options. This year’s Frederik Paulsen Arctic Academic Action Award was given to Sharon Snowshoe, Arlyn Charlie, Kristi Benson, Trevor Lantz and Tracey Proverbs for their work on the Nan guk’anàatii ejuk t’igwinjik project, which seeks to address the effects of climate change and economic development on the Gwich’in Settlement Region in Canada’s Northwest Territories.

Another example of new developments in Arctic research was moored in the docks near Harpa, namely the French Tara Polar Station, a floating laboratory which was preparing itself for operations in the Central Arctic next year. The bright orange-trimmed vessel had completed drift testing this summer, and was preparing itself to be locked into the Arctic ice for maritime and atmospheric testing. The station’s crew offered press tours during the ACA, and visitors were offered the chance to see the ship’s laboratories and facilities. The ship is crewed by up to eighteen persons, and can operate even under extreme cold conditions.

The next major Arctic Circle event will be a Forum held in Rome in early March of next year, while another major Track II event, Arctic Frontiers, will be held in Tromsø in February as the Norwegian city first starts to emerge from the polar night. It is likely that this and other like conferences will continue to focus on geostrategies in the Arctic. The aftermath of Arctic Circle 2025 opens up still another question about the Track II process in the Arctic: are these forms of diplomacy assisting government policy in the high north, or beginning to echo it?