During last month’s Arctic Frontiers conference in Tromsø, one of the more controversial ideas to appear out of the first plenary session, a discussion [video] on regional policy directions entitled ‘The State of the Arctic’, was the potential for an Arctic Treaty to reflect the changed political and strategic milieu of the high north. The issue was mentioned by Bobo Lo, a Non-Resident Fellow at the Lowy Institute in Sydney Australia and a specialist in Sino-Russian relations in the Arctic.

His comments [video] reflected concerns that present forms of multilateral governance in the Arctic were no longer keeping up with international trends, including climate change, the heightened visibility of the Arctic Ocean, the still poor relations between Russia and the West, the rise of China, and movements in many parts of the world, including in the United States, towards greater unilateralism in foreign policies. His conclusions were that these changes meant that current governing mechanisms in the Arctic would fall under greater strain, and that the time was coming for a reconsideration of new approaches which would reflect the Arctic as a global concern, including an Arctic Treaty. He stressed, however, that such a document should not erode the status of Arctic states, but rather augment it.

The concept of such a treaty is certainly not new, but it has been a longstanding bête noire in many Arctic policy circles due to its controversial nature. This has especially been the case amongst regional governments and policymakers who view any sort of ‘Arctic Treaty’ as negatively affecting the roles of Arctic states, and overcomplicating and potentially sidelining the current governance regime in the region, including the Arctic Council and the Law of the Sea. As fellow panelist Ine Eriksen Søreide, Norway’s Foreign Minister, responding to the question of whether new forms of regional government in the Arctic were required, stated, ‘we cannot give up on the structures of cooperation that are, actually, working today’. She then added, ‘if something is working, please do not try to revise it.’

Professor Lo’s remarks were later critiqued in an editorial in the High North News as falling into the trap of assuming that the Arctic was a remote and unregulated space, and that Arctic governments needed assistance with the running of their own affairs. The Independent Barents Observer took a more equivocal stance on the matter, noting that the Arctic has come under greater global scrutiny, and that other actors, including the European Union, have also been calling for an expanded international role in the region of late.

At first glance, such a treaty could be seen as advantageous in a number of ways in light of the regional (and global) changes listed above. Moreover, in theory, a treaty could act as a way of addressing perceived gaps in the current Arctic governance system, including the thorny issues of security which were purposefully left off the 1996 Ottawa Declaration, the founding document of the Arctic Council.

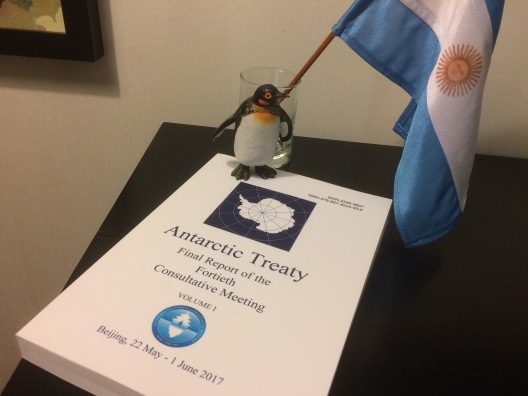

As well, it could be argued that a useable model already exists at the South Pole, in the form of the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS), created in 1959 and regulating numerous different types of activities and policies on Antarctica, including ensuring that the continent would be used for peaceful purposes only. Subsequent documents had since been incorporated into the ATS, including the 1991 ‘Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty’, (aka the Madrid Protocol), which restricts economic activity in Antarctica and prohibits extractive industry activity, (such as mining), for any reason other than for scientific study. Is it possible for the ATS to be a template for an Arctic Treaty, especially given similar concerns about the environment, security and current and future economic activities at both poles?

At the same time, some current observers such as China but also Japan, Germany and the United Kingdom have also recently stressed the growing importance of the Arctic to their strategic interests. Beijing, in its January 2018 governmental White Paper on the Arctic, stated that while non-Arctic states had no right to claim sovereignty in the Arctic, they did have the right to engage in economic and scientific activities in accordance with international law, with the document stating that:

‘The Arctic situation now goes beyond its original inter-Arctic States or regional nature, having a vital bearing on the interests of States outside the region and the interests of the international community as a whole.’

One looming question about the Arctic Council’s future is whether it can continue to balance the interests of both Arctic state members and non-Arctic observers as the level of economic activity in the circumpolar north grows.

Why so? None of the eight Arctic states define their Arctic regions strictly according to the Arctic Circle, which lies at about 66º33´N in latitude, and as such the Arctic states have their own political definitions [pdf] of where their Arctic lands begin. To give examples, the phrase ‘North of 60’ is often used to define the frontiers of the Canadian Arctic, (meaning the territories north of sixty degrees), many parts of Siberia and the Russian Far East do not fall into the traditionally defined areas of the Russian Arctic, but are now seen as such, Alaska is considered Arctic although most of it lies south of the Arctic Circle, and only one small part of Iceland, the island of Grímsey, is actually north of the Circle.

Two regional cooperation projects with the Arctic Council, the Arctic Human Development Report (AHDR) and the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) also have their own definitions [pdf] of the borders of the Arctic. As well, the post-2017 Polar Code [pdf], which regulates civilian ship traffic in the Arctic and Antarctic regions, excludes the waters immediately north of Iceland as well as north of Norway and the Russian Kola Peninsula in its area of jurisdiction, further reflecting differences between geography and politics in Arctic legal affairs. The Polar Code’s coverage of Antarctic waters, by contrast, is a comparatively neat circle bordered at 60ºS.

While it is very unlikely that an Arctic Treaty would ever be as formal as the regulations found in the EU or NATO, there would need to be an understanding amongst all of the Arctic states that any sovereignty given over to a treaty would be well-balanced by the benefits of such an agreement.

Also, the Arctic Council operates by consensus, meaning that all eight members must be in agreement before a particular new policy goes forward, and much of the day-to-day work of the Council is undertaken by the organisation’s Working Groups. There is the question therefore about whether an Arctic Treaty would upend this arrangement given the perceived greater role of non-Arctic governments within the treaty system. Moreover, Antarctica has no permanent population, thus making many legal decisions there considerably simpler, but of course the same is not true of the Arctic. About four million people, depending on one’s definition of ‘the Arctic’, live in the region, including Indigenous persons. How would an Arctic treaty preserve the status and rights of the people who actually live in the region?

All of these questions would need to be resolved to satisfaction of many parties even before the complex process of drafting an Arctic Treaty could even begin, underscoring the complexity of such a project. Yet, there remains the issue of whether the current Arctic Council configuration, as well as other regional and international laws which cover the Arctic, are enough to address the growing ‘internationalization’ of the far north in tandem with emerging security concerns. If an Arctic Treaty is not viable, are there other solutions?

Addendum (12/02/20): Kevin McGwin at Arctic Today has written a commentary on the Arctic Treaty concept, (and the ongoing political pushback), which quotes Marc Lanteigne and other regional specialists.