Since taking office in July this year, Mr Johnson has so far presided over a widening political chasm between England and Scotland, with the latter being far less supportive of Britain’s departure from the European Union. Discussion continues around a possible second referendum on Scottish independence, (the first being in 2014 which resulted in a ‘no’ vote), which the Johnson government has vowed to block, while the Sturgeon government continues view it as an option, optimally before 2021.

Despite American bombast to the contrary, the line between Arctic and non-Arctic states continues to blur with the release of the Scottish Arctic policy, along with the recent publication by Germany of upgraded strategies in the region, as well as ongoing international attention to China’s interests in the far north,.

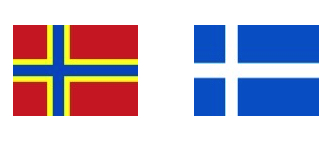

The Arctic Policy Framework was officially launched by Scottish External Affairs Secretary Fiona Hyslop in Orkney, a set of islands in Scotland’s north with deep-rooted historical ties to the Nordic region. Orkney and its northern archipelagic neighbour Shetland, were both part of the then-Danish-Norwegian Kingdom before being placed under Scotland’s aegis in the late fifteen century. Both island groups retained a great deal of Scandinavian culture to the present day.

Other highlights of Scottish history in the Arctic which the paper described in its introduction was the legacy of John Rae (1813-93), from Orkney and an explorer of the Canadian Northwest Passage. The paper elaborated on Orkney’s considerable role in the operations of the Hudson’s Bay Company trading conglomerate in the Canadian north, as well as Scottish founders of the Northwest Company, a onetime rival of Hudson’s Bay, in 1779. Borrowing a page from other non-Arctic European states with long histories in the region, including France, Italy, the Netherlands and Poland, Scotland has been seeking to develop an Arctic identity via not only modern policies but also past contacts with the region.

The policy paper was not reluctant to detail concerns that Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union may lead to a cutting of European research ties, to the detriment of Scotland’s Arctic interest. As the final deadline of the Brexit process remains set for 31 October of this year, the possibility of a ‘no-deal’ departure is very high, especially as infighting over the eventual status of the UK-Ireland border remains unresolved.

From an economic viewpoint, the report made reference to a study from April of this year, Scotland: A Trading Nation [pdf], which identified many Arctic states, including Canada and the United States as well as neighbours Denmark, Norway and Sweden as emerging high potential trading partners. Scotland’s main assets, including oil and gas, shipping, tourism, fishing/aquaculture were described as highly relevant to the emerging Arctic economy, as is the potential for high-technology ventures including internet connectivity and space research. However, the policy paper vowed that economic activities would be tempered by policies to address climate change and other environmental challenges including maritime pollution, with a promise to better coordinate with Arctic actors in addressing these problems. For example, progress in the Nordic region on electric vehicles was cited as an area of potentially closer cooperation.

As a recent commentary in the Polar Connection explained, Scotland’s Arctic policy placed a strong focus on the sub-state level, including the development of rural communities and the specific issues of local economic growth, youth, and the issue of out-migration. The protection of indigenous languages, including Scots Gaelic, was another local issue about which Scotland would be seeking communication with Arctic actors. In short, Arctic engagement is being tied to the issue of improving living standards in the regions of Scotland which abut the Arctic.

The subject of rural and island development will also be the centrepiece of a panel at the Arctic Circle conference next month, sponsored by the Scotland government, and Scottish Energy Minister Paul Wheelhouse will be hosting a plenary session at the event to further detail overall Arctic strategies. In November 2017, Scotland hosted a breakout forum of the Arctic Circle which stressed regional business development along with environmentally sustainable ‘blue growth’.

However, an editorial in the High North News stated that what Scotland was seeking in return for its ‘offer’ to Arctic actors was unclear. Moreover, the question of Scotland’s future political status, depending on the still impossible to predict Brexit process and the potential for a future independence referendum, hangs like Banquo’s ghost over the entire question of emerging Arctic engagement.

Scotland’s Arctic policy is the latest example of governments on the Arctic’s periphery, figuratively and actually, seeking a greater voice in Arctic affairs as the region draws more intense global attention. While some non-Arctic states, notably Germany, Japan, and the UK, have placed a strong focus on the state level, as well as pointing to the Arctic as a strategic asset, Scotland’s approach differs in that it examines the opportunities for Arctic engagement on many distinct levels with a greater focus on the Scottish northern periphery while at the same time framing Scotland in its entirety as an Arctic partner.